> CBC - Choice Based Conjoint > CBCT -

Choice Based Concept Test

> CBC - Choice Based Conjoint > CBCT -

Choice Based Concept Test

A hundred nothings killed the donkey.

Czech proverb

Abstract

To determine the effect of a large number of features, of which some can be optional, a hybrid procedure CBCT - Choice Based Concept Test was developed. The questionnaire consists of several query blocks. The basic block is the selection of the concept from a menu in a manner analogous to CBC. Unlike CBC, where levels of all attributes are modified and set by a computer algorithm, the profiles in CBCT are the default concepts with none or only a very few attributes modified randomly. The set of default concepts is supposed to be a representative selection of product profiles that the product provider is considering. The most often varied attribute, preferably being the only one, is the price from the close neighborhood of the default price. Each choice is supplemented with a calibration question on the probability of acquisition. This block is followed by a MaxDiff of most aspects the offered concepts are composed of. In order to estimate the acceptability of ordinary attributes (typically total prices that cannot be included in the MaxDiff block) more accurately, and to facilitate a non-compensatory simulation model, additional choice blocks may be included.

The number of attributes in a standard CBC is limited. While some authors allow up to 8 attributes our experience is up to 6 attributes seem to give reliable results. A higher number usually leads to a significant dominance of two up to about four attributes, and to low differences between the rest. It is believed uncompensated attribute levels in the generated profiles are responsible.

Complex market products are usually designed so that the attributes levels (features) are grouped. Typically, higher rank products are composed of different features than lower rank products that lack the higher level features. If the tested product is simple the modern design algorithms can be set to adapt to the design conditions.

Bypassing

prohibitions

Bypassing

prohibitions

The high number of attributes, non-compensatory decision rules and correlated attribute levels in real products, among others, have been considered as issues in conjoint analysis for several decades. Allenby et al. (2005) and Netzer and Srinivasan (2011) provide a broader review of reasons and solutions. An overview of newer procedures has not been found in the public space and it is not known that any of them have spread to common practice.

The method presented in this article is extension of the Concept and Package Tests method where the methodology based on the concepts balanced in terms of content and pricing was introduced. Its designation CBCT is partly related to CBC - Choice Based Conjoint that makes the first block of questions. The CBC block can have attributes the levels of which are selectable options or sets of selectable options. Unlike the standard CBC, CBCT still relies on the default fixed profiles designed with regard to the market. Hence the assignment CBCT - Choice Based Concept Test. Only a limited number of attributes, preferably one or two, is supposed to be modified by the CBC design algorithm, however, only in a very narrow range of values. The strategy of product classes will be applied. The top level of a nested hierarchy is made up of the default concepts at their basic levels.

The second block of the questionnaire is the standard best-worst MaxDiff of aspects of which the profiles are composed. Its purpose is to act as soft constraints in the estimation. When not all aspects besides those controlled by CBC can be included in the MaxDiff, such as quantitative or ordinary levels of some attributes (typically the total price), the questionnaire is extended with other DCM blocks known as PRIORS and/or MOTIVATORS block of CSDCA. The inclusion of such blocks depends on the actual requirements of the study.

The determination of the acceptance thresholds has been reworked to achieve a higher reliability.

As

aside to the method

As

aside to the method

Consumers make decisions based on their wishes, needs, expectations and budget limitations. They use about five decision rules concurrently: disjunctive, conjunctive, elimination by aspects, lexicographic and compensatory. For market products with many attributes, any of the rules may be influential. With exception of the disjunctive rule, they all are nearly equivalent from the view of mathematical modeling if the acceptability thresholds of the attributes are estimable.

In the suggested test method, discrete selection choices are used in all questions to ensure robust results. Scale questions are not appropriate because the values of the scale cannot be assigned an unambiguous meaning, let alone a measure. In addition, the importance of the values of any scale drifts during the survey, whether out of the respondent's ignorance or lack of interest in the product, fatigue from the surveying, etc. Unrealistic offers that appear among computer-generated profiles have a similar effect. This includes incomplete product profiles simply because they do not exist in the market. Therefore, instead of the computer-generated profiles, the present procedure uses complete fixed profiles that respect possible combinations of product aspects and represent the expected market offer. There is no doubt that an experienced product manager can create profiles that are balanced not only in terms of the aspects of a the profile, but also create a balanced scope of profiles in terms of their expected application on the market. No general algorithm is capable of doing that.

The aspect values of the profiles have about the same limitations as in the standard CBC. In addition to the classic attribute levels, there can be groups of optional items, both with the option to select a single item (a drop-down combo-box or radio-boxes) or the option of selecting several items at the time (multiple check-boxes). This arrangement significantly reduces the total number of profiles in the choice sets, because instead of fixed level values in many profiles, it gives the respondent possibility to select the most appropriate option. Each group of options is one aspect in terms of estimated parameters. The resulting information is the part-worth of the group of options, and the frequency of the selected items in the selected profiles (i.e. the conditional probability of the selection). This enables aggregated simulation of optional items in the preferential simulator.

Use of options

Use of options

The basic block in the interview is a CBC block with full concept profiles. Each choice may be supplemented with a calibration question on the probability of acquisition. However, the number of fixed full profiles designed by the managerial approach is limited. The profiles cannot be expected to be orthogonal, and, consequently, their parameters to be estimable from any number of choice tasks with sufficient reliability. To obtain additional information, the block of full profile choices is followed by a MaxDiff of individual profile aspects.

Choosing an aspect from four or five individual aspects in a MaxDiff exercise is much easier for respondents than choosing a profile from a full-profile choice set. Therefore no severe limitation is imposed on the number of choice tasks in the MaxDiff of aspects. On the other hand, the required number of full-profile tasks can be substantially lower than in the traditional full-profile CBC.

The main difference from the usual CBC is use of the acceptability thresholds. The basic results are acceptability, perception and potential of both the tested and simulated products, and their aspects. The calculation of product potential assumes non-compensatory customer decisions. Simply put, only a product whose utility exceeds a certain acceptance threshold is acceptable to the customer.

Unimportant aspects typically show off high own acceptability and low influence on acceptability of the product. Acceptability of aspects is supposed to be helpful in design of the products in different price classes.

A preferential simulator can be prepared in which the user has the option to set product profiles.

Numerical methods

Numerical methods

Balanced

acceptability of aspects

Balanced

acceptability of aspects

As

aside

As

aside

The specific outcomes of the analysis are perceptions of the aspects that compose the concepts. If homogenous user segments are known, an optimal product may be created for each segment. The acceptability of all benefits for a given segment should be balanced. The same goes for detriments, mostly prices, and fulfillment of certain conditions. The goal is to significantly reduce the probability that any of the attributes will be unacceptable to the point that it will make the entire product unacceptable. Likewise, the attractiveness of any attribute shouldn't dominate because the acceptability of a product is roughly equal to the acceptability of the least acceptable attribute.

Customers often select a compromise product because they are not interested in the least satisfying, though the cheapest product. On the other hand, they are unwilling to pay more than a certain limit or spend excessive amounts on a premium product. Based on the perceptances, and after checking in the preference simulator, the compromise products can be created as variations of the optimal product.

At the beginning of 2022, a travel insurance test was carried out. The client prepared 28 concepts based on a total of 53 fixed aspects from 13 attributes. Processed data included 514 sufficiently credible respondents.

Exclusion

of respondents

Exclusion

of respondents

There were 10 concept choices out of 3 possible in CBC style, so each respondent saw all the concepts. A calibration question on the probability of obtaining the selected profile followed each choice question.

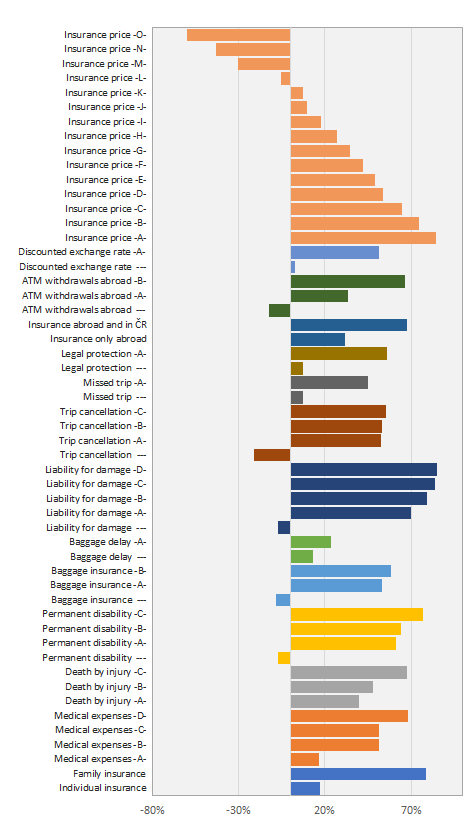

The standard MaxDiff of 38 aspects, with the prices excluded, had 18 choice tasks for both the most and the least desirable aspect of the 4 aspects. The resulting values of perceptances characterizing the average perception of individual aspects of the tested concepts are shown in the figure below on the right.

The individual aspects are grouped by attributes. Their numerical level values increase in the alphabetical order of the capital letter markers. If the attribute was not in the menu, its level is marked "---".

Contrary to expectations, the best-perceived aspects are not the lowest prices but the liability coverages. At the same time, a lack of coverage is not perceived significantly negatively, but its presence is perceived strongly positively. A welcome aspect is travel cancellation insurance. His absence has the highest negative perception. It is obvious that the lowest offered performance is sufficient for a positive acceptance of the offer. Further increase in performance does not have the expected effect.In the case of luggage insurance and permanent consequences after injury, increasing the benefit limit has no equivalent effect on their perception. Their presence at the lower level of the limit is sufficient. In contrast, differences in medical expenses, accidental death benefits, and ATM withdrawal conditions are perceived relatively strongly.

Attributes made up of only the presence or absence of a benefit can be effective as additional benefits in higher insurance categories. The absence of any of them was not detected as significantly negative.

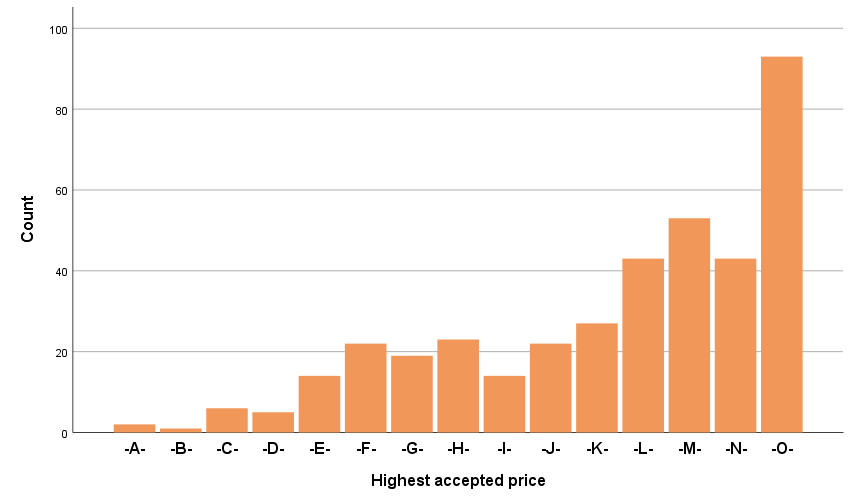

A general phenomenon observed in recent years is the growing share of customers willing to spend more for better products and services. The observed distribution of the accepted prices is bi-modal. The highest frequency at the highest price -O- might be, at first sight, an artifact of inquiry in which the respondent did not have actual expenses and reacted to an otherwise advantageous offer.

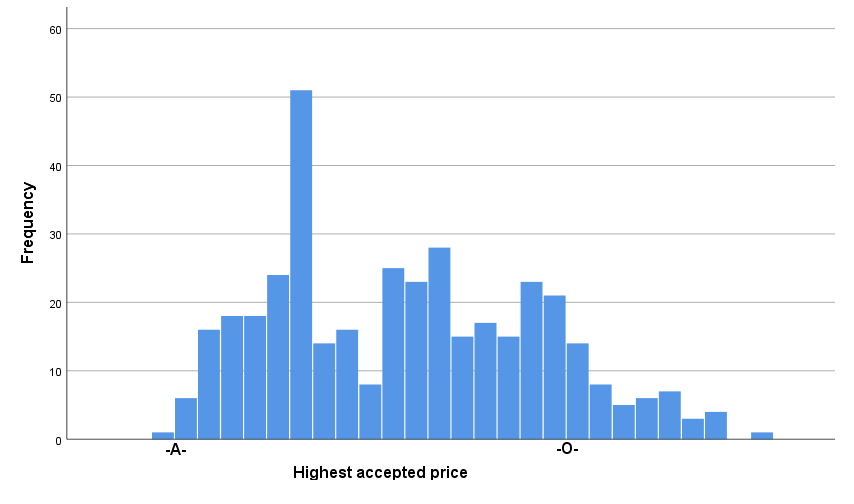

Respondents have different sensitivities to price expressed by the variability of part-worths of the tested prices. As the number of tested prices is usually limited, the histogram of observed counts is coarse. However, it is possible to randomize the accepted prices by superposition of known random part-worths (so-called sweeping). The resulting histogram on a linear price scale is below. It turns out that the distribution of willingness to accept the highest possible price is tri-modal. The frequency of the highest price -O- is split into a tail exceeding the highest price. There are individuals in the population who might accept a higher price than the highest tested price.

Poly-modal distribution of willingness to spend can be a starting point for creating compromise products at multiple price levels.

The CBCT procedure, as well as the CSDCA - Common Scale Discrete Choice Analysis, assumes the decision to select as non-compensatory below the acceptance threshold and as compensatory above it. Both procedures allow to determine the effect of a higher number of attributes than the standard CBC. The difference is in the polling procedures used. CSDCA uses isolated sequential choice and scale questions for the acceptability of individual attribute levels in the PRIORS section, while CBCT relies on MaxDiff of aspects.

It turned out that respondents in the PRIORS section of CSDCA often rejected even those aspects that were part of the product profiles they accepted. Therefore, the strategy has been changed in CBCT. Acceptance thresholds are derived from the overall behavior in selecting complete profiles and from the aspect preferences obtained from the MaxDiff of aspects. While the CSDCA in the MOTIVATORS section must be limited to incomplete computer-generated profiles (usually with the product total cost excluded), CBCT does not use such profiles at all. On the contrary, CBCT uses complete profiles designed with regard to feasible combinations of aspects with regard to the vendor expectations and requirements.

CSDCA is suitable for situations where it is not possible or expedient to prepare product profiles in advance, and for a basic screening of the future potential of the product. CBCT is useful when concrete conceptual proposals already exist and it is necessary to decide which ones to prioritize and how to optimize them.