> CSDCA - Common Scale

Discrete Choice Analysis > Preference and Acceptability in Non-compensatory Modeling

> CSDCA - Common Scale

Discrete Choice Analysis > Preference and Acceptability in Non-compensatory Modeling  > CSDCA - Common Scale

Discrete Choice Analysis > Preference and Acceptability in Non-compensatory Modeling

> CSDCA - Common Scale

Discrete Choice Analysis > Preference and Acceptability in Non-compensatory Modeling

Consumers are interested in benefits, not features.

Jeffrey Henning, Researchscape International

The gold standard of analysis and simulation in conjoint-related methods is an additive model. In discrete choice-based methods, the model is multinomial with an additive kernel composed of McFadden-type part-worths defined as logarithms of odds ratios. Consequently, a multiplicative change in odds of an aspect (a level of an attribute in conjoint) is transformed into an additive change in the resulting part-worth. Product utility is defined as a sum of the part-worths. As the model is compensatory, a sufficiently high value of any level may outweigh other levels in a simulation. There are indications that this is often unrealistic.

A remedy may be in using a non-compensatory model of simulation. These models consider preferences of all aspects of the products and their acceptability sequentially, one by one, starting with the most important must-haves (necessities) and ending with the least important delighters.

A natural measure of acceptance of a product or its profile should be a measure of a person's willingness to accept the product. However, the often used characteristic called acceptance of a profile is defined as the probability of selecting a profile from the set composed of the considered profile and a reference profile.

| Acceptance = | Odds(item) |

| Odds(item) + Odds(reference) |

By the definition, acceptance of the reference item is 50%, meaning indecisiveness which of the two items to select. When the utility of the reference profile is defined as zero, the odds of the reference item are exp(0) = 1. The formula for the zero reference utility is known as binary logit.

As

aside

As

aside

In case of centered attribute levels (so-called effect coding) the zero profile utility corresponds to a profile with all attributes set to some "middle" levels corresponding to the arithmetic mean of the attribute level part-worth.

In case of a reference attribute levels (dummy-coding), all attributes in the reference profile are set at their reference levels. So that the reference profile has an unambiguous meaning, all attributes should have a dummy level. This is often a problem, particularly with quantitative attributes such as the total price in combination with other attributes, on which the cumulative price is dependent.

The standard formula for acceptance, implemented in (all known to the author) commercial simulators, is designed for the reference profile with zero utility. Such a product is hardly a real one, let alone a referential one. The computed numerical value of product acceptability depends (inter alia) on the values of attribute levels in the study. Interpretation of acceptance is, therefore, possible only in a relative sense.

As

aside

As

aside

Acceptance formula can be formally applied on attribute levels as well but is rarely used in frames of the standard compensatory model.

In the case of centered attribute levels (so-called effect coding), the sum of all level part-worths is zero. The effects of a two-level attribute have the same value but with opposite signs. The reference value of zero part-worth corresponds to the state between the two levels and allows a reasonable interpretation. With more levels, a more common case, the meaning of a reference value is arbitrary. As the information on preferences between levels of different attributes is not available, acceptances computed from them provide it neither.

In the case of a reference attribute level (dummy-coding), the effect of one of the levels is set to zero, and the effects of all the other levels are related to it. Therefore the reference level is often set as the most common one, the current market one, and alike.

Preferences between levels of different attributes can be obtained by putting all part-worth on the same scale as is done in CSDCA - Common Scale Discrete Choice Analysis. However, the acceptability of the aspects is still unknown as the common scale has no real meaning. A remedy can be achieved by adding a formal (invisible) level of acceptability threshold to each attribute and ask respondents which levels are acceptable and how much. Then each attribute can have its scale that represents both the preference among all attribute levels and their acceptability.

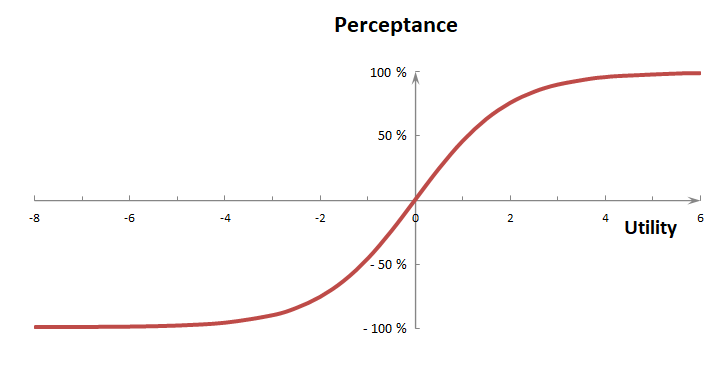

To assess the degree of acceptability of aspects (levels of attributes) we propose a quantity called perceptance to express perceptional acceptance. It is linearly related to acceptance, is zero at the threshold level, -1 (-100%) for an absolutely unacceptable, and 1 (100%) for a fully acceptable aspect:

| Perceptance = | Odds(aspect) - Odds(threshold) |

| Odds(aspect) + Odds(threshold) |

As

aside

As

aside

Positive values indicate attractiveness or willingness to accept the aspect, and negative values are a measure of its unacceptability, repellency or rejection. The zero threshold value is related to an indifferent view of the aspect. The main advantage of determining the perceptance is the possibility to compare aspects from different conjoint attributes which is not possible when the usual effect coding is used. However, reliability of the threshold estimate is crucial.

If the reference utility value is zero interpretation of the perceptance is simple. Odds of the reference is 1

and the perceptance is a difference between an acceptance value and its complement (non-acceptance value):

A perceptance value is linearly proportional to the probability of selecting an aspect from the binary set containing the aspect and the threshold. We take the perceptance for an implicit probability of accepting the aspect. Provided a product is understood as a bundle of aspects all being positive and independent in their evaluations, perceptance of the product can be estimated as a weighted product of the aspect perceptances. This gives a way to formulate a non-compensatory model of choice.

As

aside

As

aside

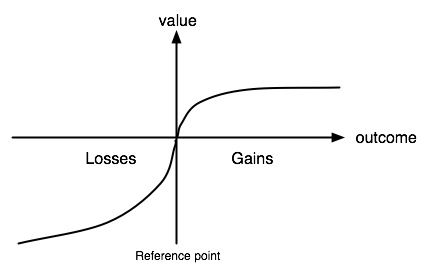

In non-compensatory models of choice, a product is treated as a bundle of aspects that are (in the simplest case) considered independently one by one. In conjoint design, mutually exclusive aspects are grouped in a product attribute. In view of Kahneman and Tversky's prospect theory, an attribute level of a chosen product can be considered as an outcome of the choice. By choosing a product with several aspects, the outcomes are obtained simultaneously.

Kahneman and Tversky introduced two major elements into the utility theory. First, the outcome perceived value has a marginally decreasing increase with an increase of a possible gain. Second, people tend to think of a possible outcome relative to a certain reference point, often the status quo or an expectation, rather than to the final status. The perceived value is positive only if the gain exceeds this reference point, otherwise, the outcome is perceived as a loss. At the same time, people tend to overweight exceptional, but rarely offered positive aspects, and underweight the aspects common to many offers on the market. Discrete choice experiments give us a way to uncover these factors.

All qualitative non-compensatory models of choice assume a choice accompanied with a loss will not proceed. Such an offer is simply ignored by the decision maker. The same is true for a discrete choice experiment. Therefore, quantitative evaluation of the loss branch in DCM modeling is not critical. Estimation of the value for the gain branch is important. If it is assumed proportional to the perceptional acceptance (i.e. perceptance), the prospective reference point can be replaced by the threshold odds, and gains by partial odds of the aspect. Perceptance has the most important properties required by the prospect theory:

As

aside

As

aside

| Rank | Location | Transport |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spain | by plane |

| 2 | Spain | by car |

| 3 | France | by plane |

| 4 | Italy | by plane |

| 5 | France | by car |

| 6 | Italy | by car |

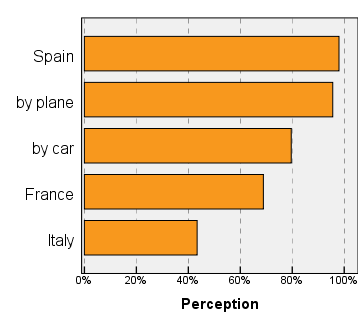

In connection with non-compensatory analysis and modeling, A. Dieckmann et al. (2009) discuss the lexicographic-by-aspect analysis and simulation, and give a simple example. Given holiday options differing in a travel location, with the three aspects Spain, Italy, and France, and means of transport with the two aspects plane and car, a person may express the preference order shown at the right.

The person prefers Spain regardless of how to get there. Means of transport becomes determining when considering other countries, with a preference for flying. The aspect sorting order is [Spain - plane - France - Italy]. The controlling aspects of the lexicographic selection path are shown in pink. Dieckmann et al. state this result would be produced by the lexicographic-by-aspects implementation of the greedoid algorithm.

The above example is a result of a full ranking of a complete set of profiles with 2 attributes: the 3-level location and 2-level transport. To obtain quantitative perceptances suggested in this article, we have extended each attribute by adding a just unacceptable level. Ranking in the complete set of (4 x 3 =) 12 profiles was kept the same. The 6 additional profiles containing the unacceptable levels were considered as refused by the person and were given a tied rank 7. The part-worth were computed using hierarchical Bayesian estimation. The resulting perceptances of the aspects from the are in the picture at the right.

As

aside

As

aside

| Rank | Location | Transport |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spain | by plane |

| 2 | Spain | by car |

| 3 | France | by plane |

| 4 | Italy | by plane |

| 5 | France | by car |

| 6 | Italy | by car |

The complete aspect sorting order by perceptances is [Spain - plane - car - France - Italy]. It is different from the greedoid preferences of the aspects: car and France have reversed order. This is because car appeared in a higher ranked choice than France. However, this difference has no effect on simulation of the ranking exercise and the result is identical. The controlling aspects in lexicographic selection path are shown in green.

There is an important point to consider. We have two aspect orders leading to the same item selection. On one hand, different methods of analysis may provide different results. On the other, a robust way of simulation may lead to a correct result.

The extreme values (-100%, 100%) of the perceptance are pure limits and are not achievable in practice. Differences in utilities corresponding to very high or low acceptability values have a lower effect on the difference in the perceptance than in the vicinity of the values commonly encountered by the consumer.

While the McFadden-type utility corresponds more to physiological perception (see Wiener-Fechner's law), the perceptance corresponds more to the perception of market offers. It is common knowledge that increasing the acceptability of some aspect above a value that is already sufficiently satisfactory does not have the expected effect on the customer's decision. On the other side, it makes no difference from the seller's view if the product was rejected due to a just unsatisfactory aspect or a very unsatisfactory aspect. If the aspect is just an unsatisfactory one, a mild increase in its acceptability may be sufficient to make the aspect perception indifferent and the product acceptable.

Knowledge of the degree of acceptability of aspects can be a guide in designing compromise offers in different

price classes. It allows to adjust product aspects to have the appropriate, usually roughly the same,

acceptability values for a given price.

Extending attribute levels with a perceptional threshold level brings in a new possibility of interpretation. A quantitative essence of the attribute level perceptance can reveal either a positive or negative influence on the product acceptability. The values are simple to understand and may be useful in managerial decisions. Their implicit use is in OBIMA - Object Image Analysis. Their explicit graphical presentation may replace the usually difficult-to-understand presentation of attribute level part-worths.

When attribute level sorting is combined with preferences between profiles composed of attributes, such as in CSDCA - Common Scale Discrete Choice Analysis, perceptances usable in non-compensatory simulations can be obtained.